Build A Simple Terminal Emulator In 100 Lines of Golang

A tiny codelab to help you understand how terminal emulators work.

Photo by Sai Kiran Anagani on Unsplash

TTY stands for TeleTYpe. If you Google the word teletype, a picture of a device that looks like a typewriter shows up. How did a typewriter become an essential part of the Linux operating system?

The teletype came about through a series of innovations around message transmission on electric channels. It has a rich history going back to the 1840s. Several innovations and collaborations led to the development of the Telex exchange network in the late 1920s. Telex eventually grew to over 100,000 connections worldwide and was vital in global communication post World War II.

Meanwhile, computer technology was progressing. Earlier computers could only run one program at a time but in the 1960s, multiprogramming computers appeared on the market. These computers could interact with users in realtime via a command-line interface. There was suddenly a need for input and output devices. Instead of building new I/O machines, pragmatic engineers reused existing teletypes. Teletypes were already on the market, and they fit the use case perfectly as physical terminals for mainframe computers.

Users could now type commands on the teletype and receive the computer output via punched tape. Later versions of the teletype were completely electronic and utilized electronic screens. Users could move the cursor and clear the screen, features unavailable on printed paper teletypes.

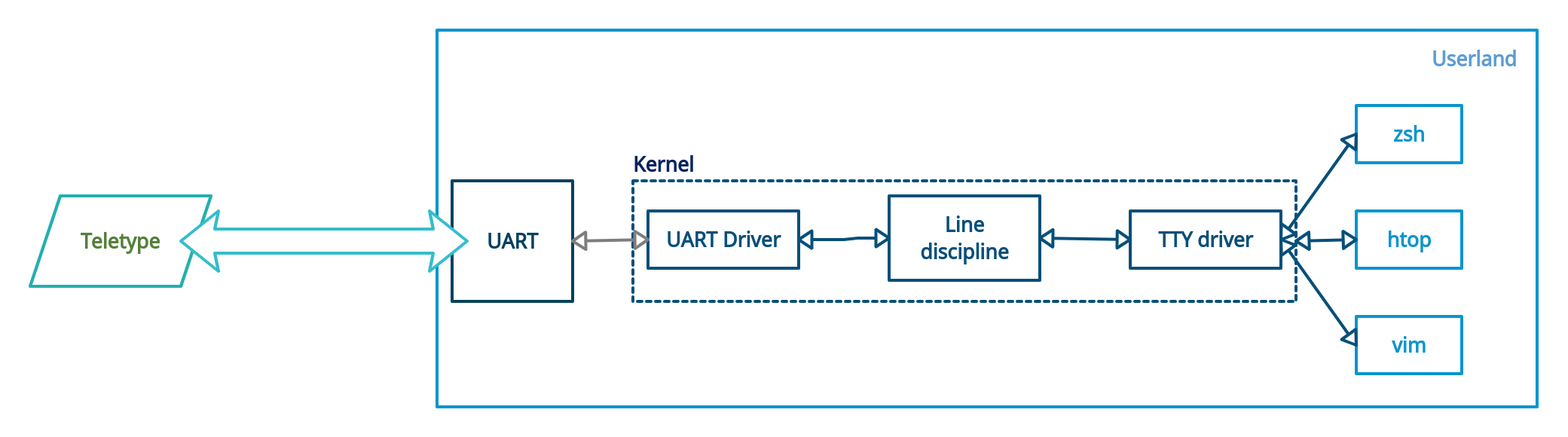

A physical line connects the teletype to the Universal Asynchronous Receiver and Transmitter on the computer. This physical line consists of two cables, an input and output cable. When a user types on the terminal, the input cable sends the keystrokes to the UART driver, which sends the keystrokes to the line discipline layer. The line discipline does three things:

When the user presses the enter key, line discipline sends the buffered characters to the TTY driver, which passes the characters to the foreground process attached to the TTY. The UART driver, line discipline, and the TTY driver make up the TTY device.

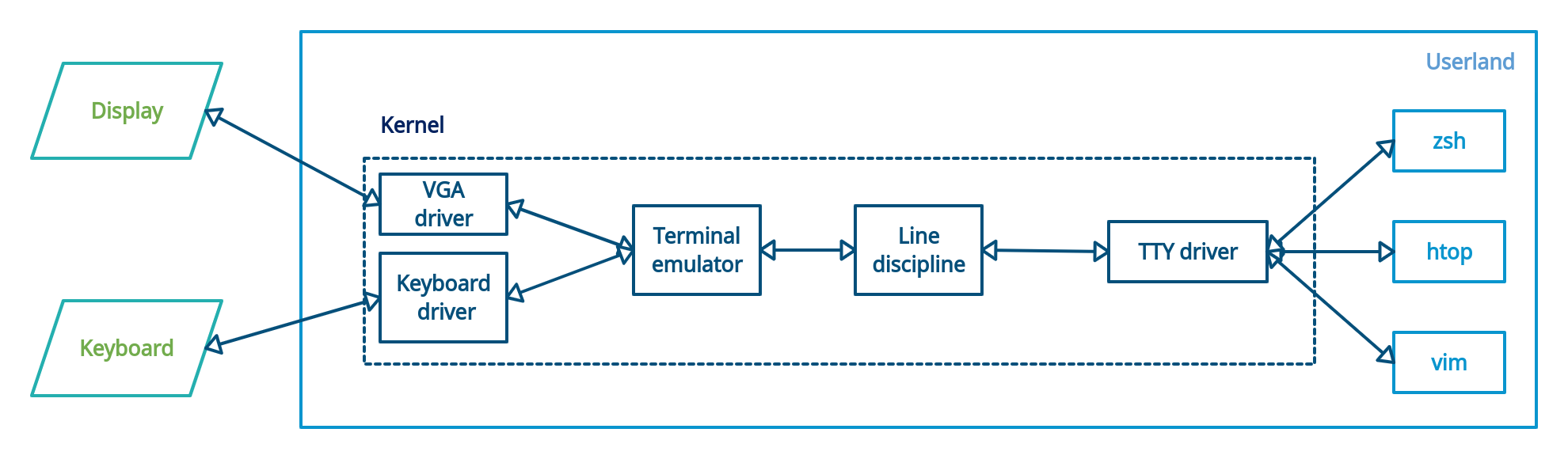

As technology improved, computers shrunk in size, and teletypes became cumbersome. Software emulated teletypes replaced physical teletypes. These terminal emulators work in the same way as their physical counterparts, the only difference being that there are no physical lines and UART connections. Examples of terminal emulators include xterm and the gnome-terminal.

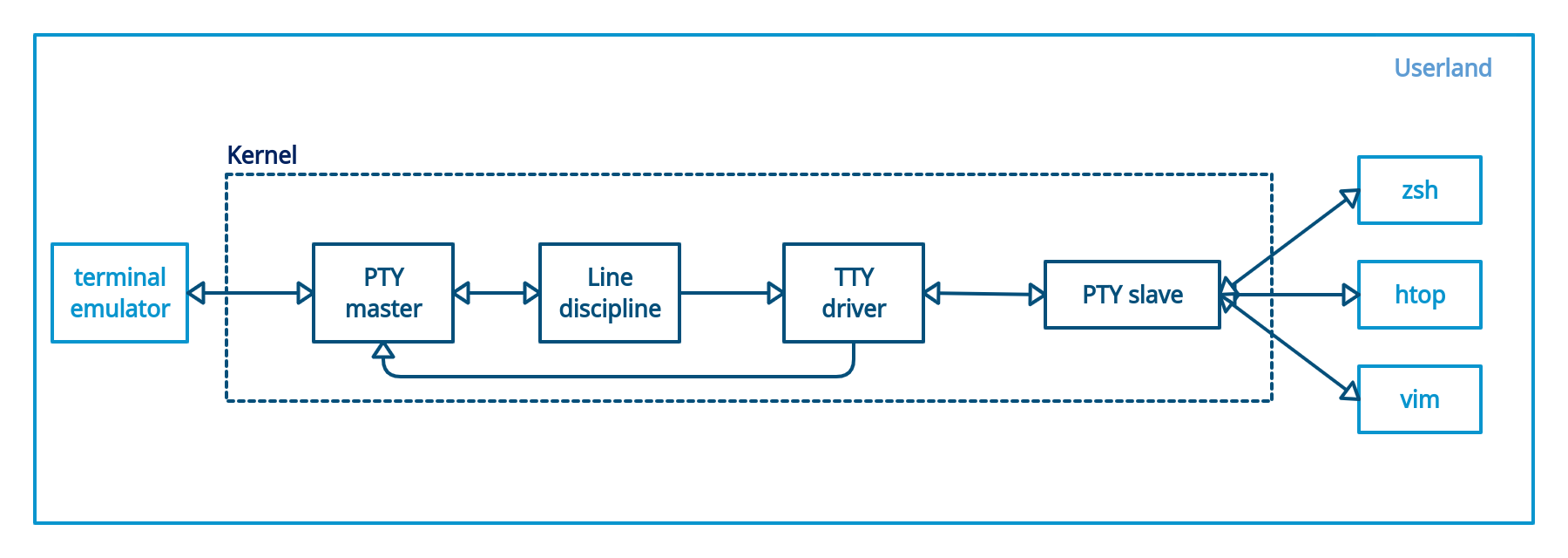

The whole TTY subsystem residing in the kernel made terminal interactions inflexible. The solution was to move terminal emulation to the userland, leaving line discipline and the TTY driver intact in the kernel. The PTY consists of two parts:

Note: the line discipline instance is not evoked when the TTY driver is sending user program output to PTY master.

So far, we’ve covered terminal emulators and pseudo-terminals. The shell is a program that resides in userland and manages user-computer interactions. Examples of shell programs include bash, zsh, and fish.

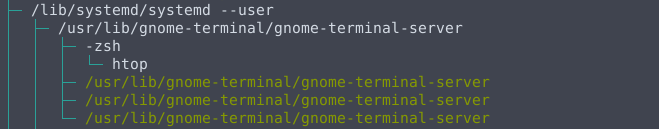

What happens when you open a terminal emulator on Linux? I’ll give an example with my environment: I use gnome-terminal as my terminal emulator and zsh as my shell.

Systemd is Linux’s system and service manager. As shown above, systemd spawns a gnome-terminal subprocess, which in turn starts a zsh subprocess. The output above is from htop, which I ran from my terminal emulator. So, what happens when you run a command on a terminal emulator?

This was a brief introduction to the Linux TTY subsystem. Much of how it operates right now is influenced by technical decisions made over 60 years ago. Remarkable resilience. If you have any remarks or feedback, please reach out on twitter!

Technical references: