A fallback is defined as a contingency option to be taken if the preferred choice is unavailable. Hover is an Android SDK that automates existing USSD sessions in the background of Android applications. We will set up a USSD channel (with a USSD backend), configure an action on the Hover dashboard and integrate the action as an offline fallback in an Android app.

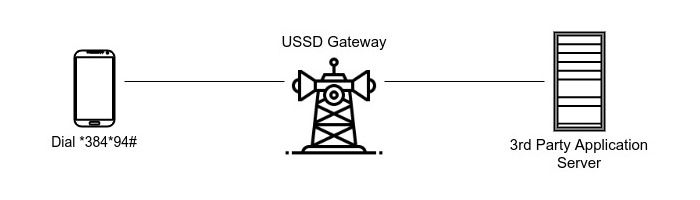

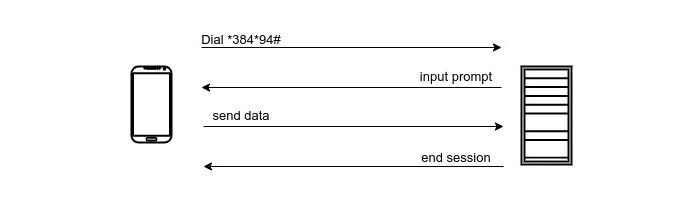

USSD has two modes of operation, USSD PULL, which is mobile initiated and USSD PUSH, which is network initiated. For this fallback use-case, we’ll be using the mobile initiated mode to communicate data between the app and server. The USSD protocol will serve as a transport layer and USSD messages will be the data packets communicated between the app and the server. Hover will be the “USSD client” for the Android app, capable of sending and receiving USSD messages.

The maximum number of characters in a USSD message varies between carriers. Safaricom (KE) has a limit of 160 characters sent from the network from the user and a user input limit of 80 characters. Similarly, USSD session length varies between 90-180 seconds, depending on the carrier.

Architecture

For the purpose of this demonstration, we’ll be sending a set of key/value pairs to the server. The flow involves four messages sent between the mobile app and the server:

- Mobile dials USSD code, initiating a USSD session

2. Server responds with the messagesend data, awaiting input

3. Mobile sends url query string

4. Server receives and persists the data; responds with a final success message

We’ll use the Hover SDK to automate these four steps.

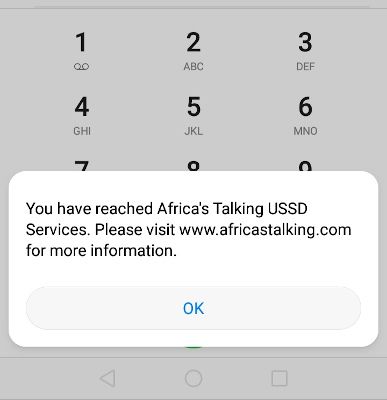

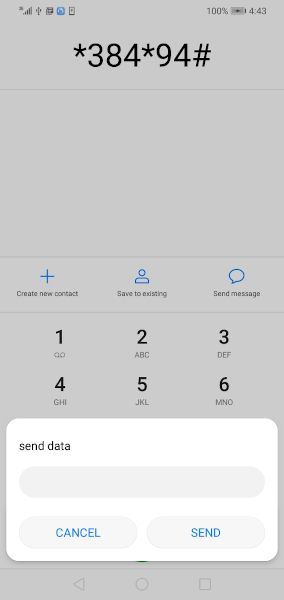

The USSD Gateway

The first step is setting up a channel on the USSD Gateway. Unlike most protocols, USSD channels are limited to the country/region that the providing telecommunication company operates in. For the purpose of this demo I’ve used a shared USSD channel, * 384 *94#, provided by Africa’s Talking. This short code is only available on Safaricom (KE) and Orange (KE) networks. Dialing the USSD code gives us the following message:

That’s because we haven’t set up the callback function that will read and respond to USSD requests. USSD response messages are in plain text beginning with the keyword CON if the session is ongoing. If the response message is the last for the session, begin with the keyword END. A simple USSD callback function that responds request with the message Welcome to Hover would look like this:

# Python 3.8.2

func ussd_callback() {

return “END Welcome to Hover”

}The complete callback function for the architecture described above (image 1.2) looks like this:

import urllib.parse

def save_report(event, context):

params = urllib.parse.parse_qs(event['body'], keep_blank_values=True)

if 'text' not in params:

return {“statusCode”: 400, “body”: “END bad request”}

text = params['text'][0]

# Respond with the text `send input`, expect data

if text == '':

return {“statusCode”: 200, “body”:“CON send data”}

# Parse url query string

data = urllib.parse.parse_qs(text)

# If the data sent is malformed, respond with `bad request`

# and end the session

if not bool(data):

return {“statusCode”: 400, “body”: “END bad request”}

# Process, persist, analyze data

# End session, `success`

return {“statusCode”: 200, “body”:“END success”}The example above is Python 3.8.2 code deployed as a serverless function on AWS. I won’t dig deep on setting up a callback function in this blog post because a lot of the technical input is subjective based on language choice and deployment options. Africa’s Talking USSD API sends a post request to your callback function with five parameters as described in their documentation. In the example, we read the text field, which contains the user input. If the text field is empty then that means the session has just been initiated and the function responses with CON send data. Otherwise, we try parse the text field (assuming it’s url encoded) and end the session.

Dialing * 384 *94# now gives you the following messages:

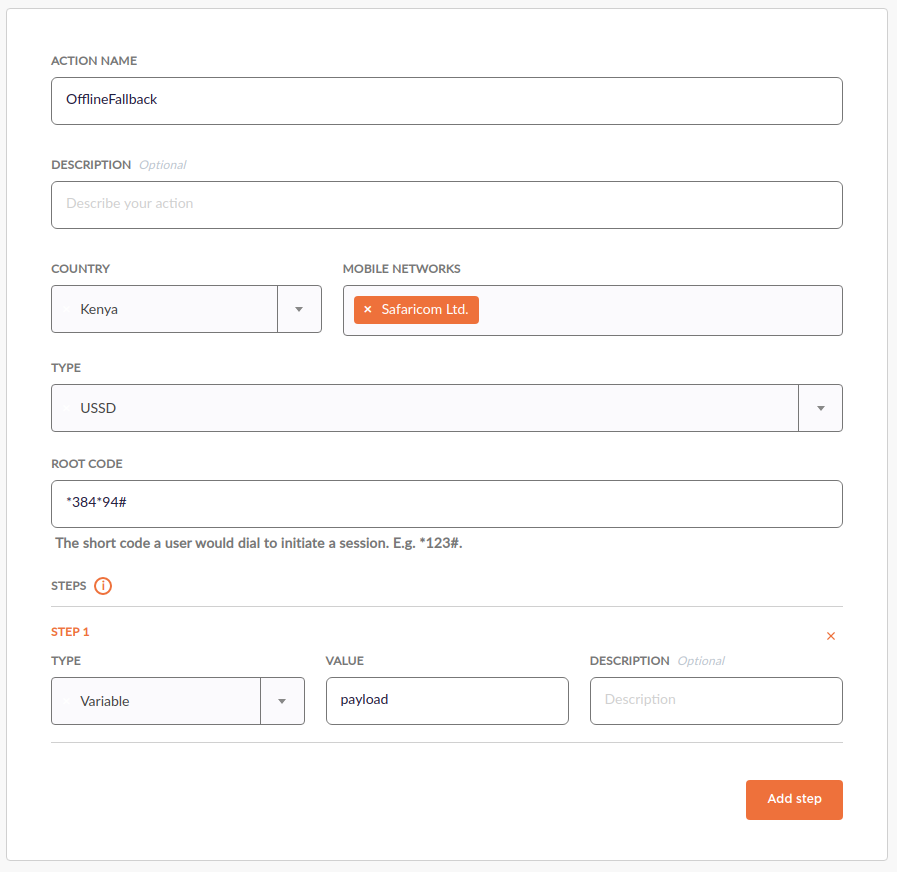

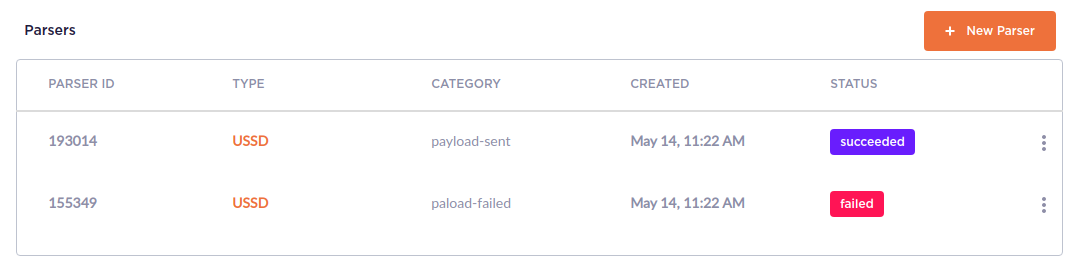

The Hover Dashboard

Now we have a mature USSD interface that we can use to send data to our backend. The next step is integrating Hover to automate interactions with this interface. If you’re not familiar with creating actions and parsers on our dashboard, you can read through our documentation.

The image above is an action configuration for our USSD interface. There’s one step configured, a variable that’s a direct response to the send data prompt.

sendData.setOnClickListener {

var payload = “”

if (report_title.text.isNotEmpty()) payload = “message=${report_title.text}”

payload = if (hungry.isChecked) {

payload.plus(“;hungry=1”)

} else {

payload.plus(“;hungry=0”)

}

if (intensity.text.isNotEmpty()) payload = payload.plus(“;intensity=${intensity.text}”)

// Input from a RatingBar

payload = payload.plus(“;mood=${mood.rating}”)

if (payload.isNotEmpty()) {

val i = HoverParameters.Builder(this)

.request(ACTION_ID)

.extra(“payload”, payload)

.buildIntent()

startActivityForResult(i, 0)

} else {

Toast.makeText(this, “Nothing to send!”, Toast.LENGTH_LONG).show()

}

}The example above is in Kotlin and it demonstrated how you can run the action we created before with a valid payload. In this specific case, a valid payload means a URL encoded key/value pairs separated by a semicolon. Example:

activity=idle;course=818;altitude=1780.91;path=Ngong+roadAfrica’s Talking’s USSD API posts query string encoded parameters to the callback URL and the individual parameters are separated by an ampersand (&). This means that we can’t use the ampersand (&) in our query string that will sit in the text parameter, that’s why I’ve intentionally used the semicolon separator in the schema above. The semicolon separator is illegal according to the 2014 W3C recommendation but Python 3 still supports it.

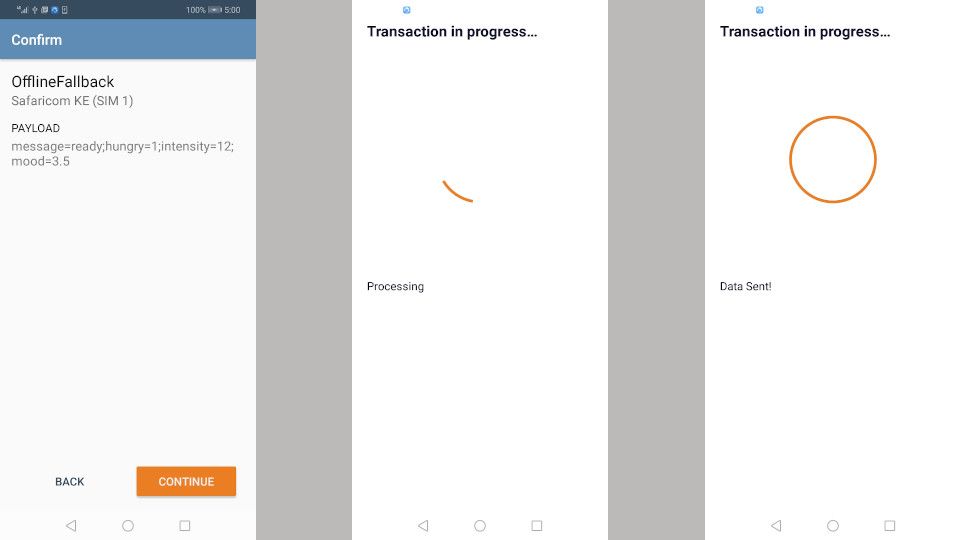

Running the action described above (on an Android phone with no internet connectivity) will result in the following screens:

Conclusion

This demonstration shows how you can send data from an offline phone to your server but since the flow of data is bidirectional, you can also send a payload from your server to your app.

Due to the restrictions in message size and session length, you can only send lean data via USSD. I used the query string schema because of the limited payload size but any schema/encoding can be used as long as the payload size is not exceeded. You can send multiple messages in sequence as long as the session is still valid. This means that you can implement a chunking algorithm to send data in sequence.

Originally posted on the Hover blog.